Jan Morris is one of my favorite authors. Her writing has inspired me to become an avid traveler, a student of history, and a global citizen. I actually met Morris at a bookstore in Hong Kong in the early ’90s. After queuing for several minutes, I handed her a copy of Hong Kong: Epilogue to an Empire to sign. Seeing her face-to-face was disorienting because, having read several of her books, I felt I knew her personally. Her husky voice and broad shoulders should not have surprised me, yet I wasn’t prepared for it. It was ironic that Morris (an outsider) has written a book on Hong Kong that helped me (a local) appreciate the place of my birth.

Although Morris’s books are usually shelved in the travel writing section, she is much more than a travel writer. She is a storyteller, a memoirist, a historian, but most importantly, she is an optimistic wanderer who always extends grace to people regardless of their origins or circumstances.

I read her book on Hong Kong when I was in my 20s. Morris introduced me to some of the characters and events that shaped the city. From Captain Charles Eliot to Sir Run Run Shaw, from the Esing Bakery poison bread incident (an attempt to kill all the westerners since the locals didn’t eat breads) to the heroic but futile defense against the invading Japanese force in WWII, from the influx of merchant refugees from Shanghai after the Chinese Civil War to the inundation of boat people after the war in Vietnam, in her elegant prose, she vividly captured them. Aside from historical figures, dates, and events, what inspired me was how Morris chronicled history. She would juxtapose the glamour of the rich with the suffering of the poor. She would be equally at ease speaking with the last Governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, or conversing with an expat nursing a beer in Lan Kwai Fong. She highlighted the complex social fabric resulting from a blend of Eastern and Western culture, yet she would not shy away from its contradictions and conflicts.

In Morris’s words: “Life has its problems but it also has its delights.“

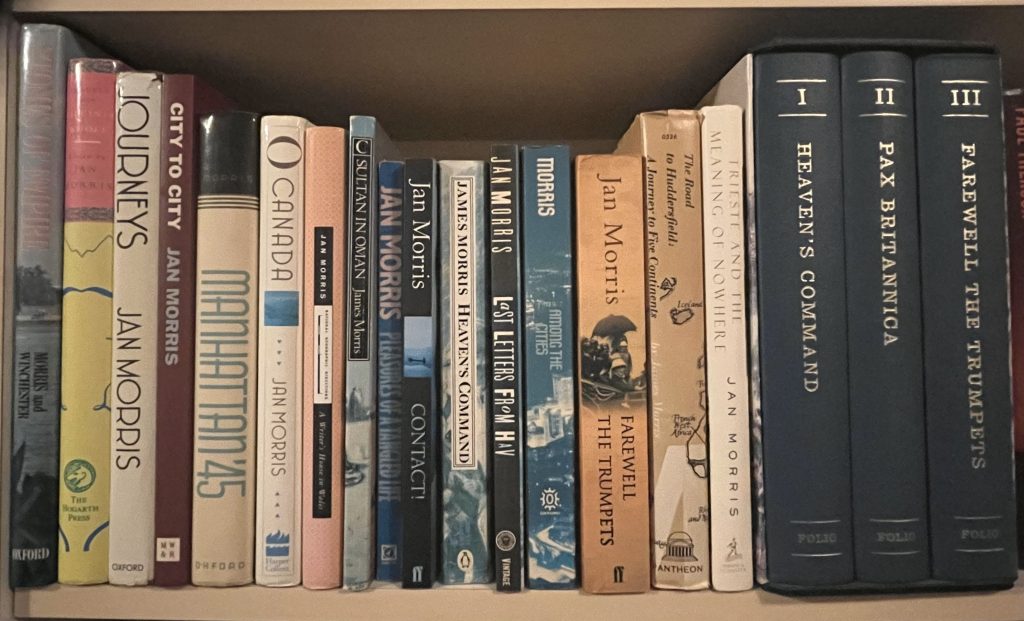

On the bookshelf in my house, there is a row of books by Morris: adjacent to Hong Kong: Epilogue to an Empire, there is a copy of Trieste: The Meaning of Nowhere. She once said that the Trieste book would be her very last. She wrote a few more after that and left us with more than forty books. I purchased the Trieste book at the now defunct Book City on Bloor Street in Toronto some years ago and promptly finished it over a weekend. After I put the book down, I knew I needed to visit the city one day. In March of this year, I made my sojourn to Trieste, and although it was my first visit, I felt at home there. Taking a 2-hour bus ride from Ljubljana to reach Trieste turned out to be a fine choice because it afforded me a literal bird’s-eye view of the city.

Walking from the bus station to my hotel, I passed by the Canal Grande, admiring the Church of Sant’Antonio Nuovo and the Serbian Orthodox Church of Saint Spyridcaon (though somehow not spotting the life-size statue of James Joyce). Less than 10 minutes later, I found myself among a throng of pedestrians at the Piazza della Borsa. Just when I thought I had seen the heart of the city, Piazza Unità d’Italia, with its impressive neoclassical buildings and a view of the Adriatic Sea, made its appearance.

For the following 48 hours or so, I wandered around the city on foot using a self-guided walking tour I purchased from the Tourist Information Centre and suggestions from the hotel staff. In terms of sites, other highlights for me included the Roman ruins (aren’t the Romans in every old city in Europe?), the historic Caffe San Marco, where Italian intellectuals have lingered over a cup of fine coffee since 1914, the Trieste Synagogue, or the Great Temple, which once served a sizable Jewish population, and the grandeur of the 14th-century Cathedral of San Giusto, built on the site of an old Roman temple.

Many of these sites were stunningly beautiful on their own merits, but I learned so much more from Morris about this once thriving duty-free seaport. Because of its geographic location, with access to the sea, during the height of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, goods such as coffee, sugar, spices, textiles, grains, and timber were traded among countries from the Middle East, Asia, and the Americas. Because of the trade, Trieste became a meeting place for Austrians, Ottomans, Serbs, Italians, Croats, and Jews. Although the power shifted from time to time, the merchants found a way to live and work together. Almost everyone was a minority who came from somewhere else.

In the book, Morris wrote: “They are not inhibited by fashion, public opinion or political correctness. They are exiles in their own communities, because they are always in a minority, but they form a mighty nation, if they only knew it. It is the nation of nowhere, and I have come to believe that its natural capital is Trieste.”

Maybe because of her own experience, I think Morris truly understood the meaning of exile. From her book Conundrum, a personal account of her gender transition, she wrote about how it felt when she realized she had been born in the wrong body. After her operation, one that might have been illegal in the UK at the time, on her return flight home from Casablanca, she lamented the fact that she would have to resign (or be expelled?) from a number of private clubs, though she added she would probably still socialize with her friends there, only now as a guest rather than a member. Maybe being a perpetual exile made her an empathetic traveler. From the books I read by Morris, I learned, either explicitly or implicitly, that stereotyping is not necessarily inaccurate, but it is certainly not the whole picture. I learned that too much sensitivity could become insensitive. In the words of Ted Lasso (definitely not Walt Whitman): be curious, not judgmental.

Back to the Trieste book, there is a chapter called “The Nonsense of Nationality” where Morris dives into the topic of race and nationalism. Morris argued, “race is a fraud … and nationality is a poor pretense.” I couldn’t agree more because, in terms of race, humans are genetically similar, sharing more than 99% of the genetic code with one another. We may have different ethnicity, but we are certainly of one race. In the same chapter, Morris wrote: “You can change your nationality by the stroke of a notary’s pen; you can enjoy two nationalities at the same time or find your nationality altered for you, overnight, by statesmen far away.” Indeed, far too many people speak of citizenship as if it is something they earned rather than were born into.

When I visit a new place, I spend my time admiring its architecture, learning its history, sampling its cuisine, absorbing its ambiance, and, if I am lucky, having conversations with some locals that goes beyond the superficial greetings. I enjoy solo traveling because I can focus on the new surroundings on my own schedule and itinerary. However, on this trip, I sometimes sensed the spirit of Morris, moseying along just a few steps ahead of me, chatting with a vendor. And a few minutes later, sitting at a sidewalk café, sipping a spot of tea rather than a cup of coffee.

Jan Morris died on October 20, 2020; I think she is still traveling in the great beyond.

“If you are not sure what you think about something, the most useful questions are these,” she says. “Are you being kind? Are they being kind? That usually gives you the answer.”

~ Jan Morris as quoted by Tim Adams in a Guardian article.

Photos of Trieste, Italy

Related pages: